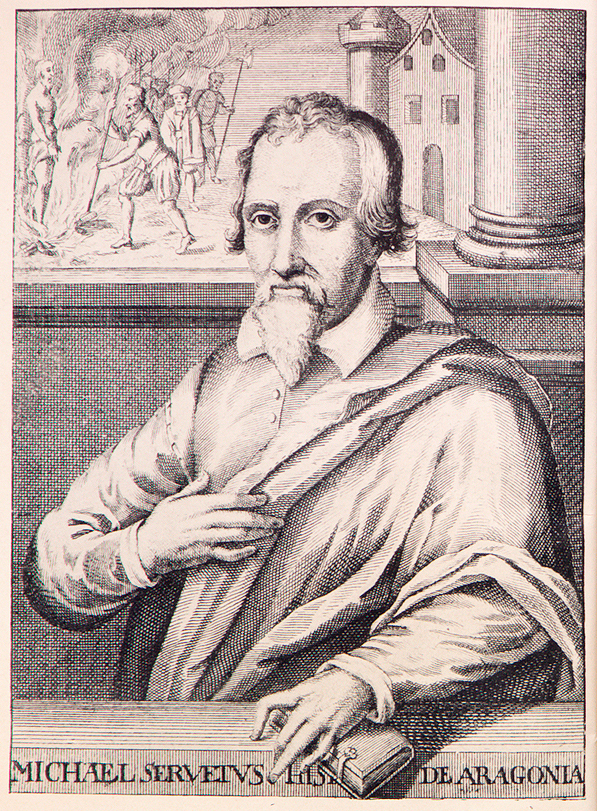

Michael Servetus, used with permission

Let's talk about heresy.

The word heresy has been in the news the past few days. It's been used to describe pretty much any opinion Rob Bell has to share. And it's not a charge to be taken lightly. Certain modern cultures still quickly levy execution against blasphemers. And even the occasionally celebrated Geneva Consistory might have to be exhumed to apologize for their capital discipline against Servetus, despite the apparent legitimacy of the charge.

But we don't live in the Middle East. And we don't live in 1500s Geneva. Most of us live in contemporary Western culture, enlightened by the Enlightenment, jaded by moral relativism, and easily distracted by advertising, corporate interests, and the office March Madness bracket. And we like to think that we're cautious. And fair. And kind. And that we don't have prejudices.

But we know better, don't we.

Unless you've been living under a rock for the past few weeks, you probably heard that Rob Bell has a new book out. It came out Tuesday. It was #8 at Amazon before it came out (#3 now as this is being written). Go figure.

And unless you've actually read it, you probably think that it's full of blasphemy. Because you've heard that it is. (To be fair, actually, you may think that it's full of blasphemy after you read it, too. I wouldn't know. I haven't yet.) And you've heard that Bell is a universalist, which is apparently an unpardonable sin (ironically?), so you think that's true, too. (A universalist is a Christian who believes that every human being will be welcomed into eternity with God regardless of their decision for or against Christ in their lifetime.)

So, assuming that you're comfortable with forming an opinion about something before you know what you're talking about, let's just go ahead and list all the possible prejudicial statements you might be able to make:

- Rob Bell is completely off the mark and never says anything legitimate or worthwhile.

- Rob Bell is right on the money and everything he says is gospel.

- Rob Bell understates his case. He's light on substance and doesn't really say anything new.

- Rob Bell goes a bit too far at times, but is otherwise reasonably palatable.

Now, since we all know that we contemporary Christians are supposed to be proud that God didn't make us like that heretical blasphemer, Rob Bell, let's rise above making extreme statements and toss out the first two because of their unqualified adjectives. That leaves us with the last two to choose from.

And I don't think we can really choose between them, mostly because both of those remaining statements should remind us of us.

Here's the problem: Christian theology is a living organism, an ongoing, constant conversation, an unanswered question posed to the panel for discussion (and we're all in the symposium), a milieu of opinion that responds to dogma and actualizes it into something full of meaning and relevance and usefulness to a particular culture. It moves. At its best, it moves in the influence of the wind of God. At its worst, it is as corrupted as we are. We corrupt it.

We and Bell are in the same boat, hoping that we've got it right, trying to make sense of ideas that we don't own, that have been around a lot longer than we have, that will outlast us, and that, frankly, are beyond our comprehension. We are incapable of circumscribing the mind of God. (If you don't believe me, consider what happened to Job when he thought he was entitled to give it a try.)

That being said, we're probably behaving well when we temper our ounce of judgment with an ounce of margin to hear retellings of details and opinions that we've been slow to listen to.

Here's the thing. Bell's been accused of espousing universalism, a charge which he denies. He says our response to Christ is important. He doesn't deny that hell exists. He does apparently question whether hell is a place God assigns certain people to, or a reality they create for themselves by denying him, but this isn't anything C. S. Lewis didn't say before him. Lewis was hardly a universalist, nor even a theological liberal. Madeline L'Engle was a universalist. She's the one who wrote, "All will be redeemed in God's fullness of time, all, not just the small portion of the population who have been given the grace to know and accept Christ. All the strayed and stolen sheep. All the little lost ones."

A lot of people are very uncomfortable with that idea. Bell's never said that. Quite the contrary, he's apparently uncomfortable with that, too.

We live in a culture that's quick to judgment, that responds to perceived injustice with war, that confronts political adversaries with insults, that wants to deprive undesirables of basic human rights, and that's inexcusably fond of accusing everyone but ourselves for the systemic problems that we have to overcome. In short, we love to convince everyone that our understanding of things is right, and we hate it when anyone has a problem with us because they think ours is wrong.

And then we have a problem with someone coming along and saying that God offers us an infinite love as a correction to our mutually exclusive, unqualified certainties? We don't want to hear that? We don't want to find out that the central message of God's word is love?

No, probably not. We want to hear that he saves us, but that he doesn't save the other guy, the guy who ticked us off.

Bell's book is a submission to the conversation. He's a pastor. He works with confused people who have distorted views of love and salvation and hope and joy, and they need a handle. (They're people a lot like us.) He's not interested in giving definitive answers, so we shouldn't be so upset if he doesn't. He's interested in throwing a bunch of pasta at the wall and letting the rest of us see what sticks.

What should our response be?

I don't know. I haven't read the book.

But I know that it should:

- Include discernment. We're to test the spirits, not dismiss them before we listen to them.

- Be deep. We reach a point where it's time to move past the milk, and ponder spiritual meat, some new ideas that would have left our heads spinning when we started out. We'll never get a chance to hear those ideas if we're unwilling to listen to things that, at first glance, we disagree with.

- Be intentional. We are supposed to make every effort to watch our life and doctrine closely. If life and doctrine are supposed to mesh, then maybe we should get some information before we form the sorts of opinions that lead us to make character accusations on our fellows.

The real heresy is not listening. God gave us brains and hearts. Let's use them.

Watch the Rob Bell interview with Lisa Miller on the eve of the book release

on lovewins at livestream.com

on lovewins at livestream.com

This guy doesn't listen very well